Wanna Cry Ransomware

- mike

- May 20, 2017

- 4 min read

As day four of a globe-spanning cyberattack brought with it a marked slowdown in the spread of infected computers, governments and companies started to count the costs. Hundreds of thousands of users were infected by a strain of so-called ransomware, called WannaCry, that scrambled files of victims and demanded ransom via bitcoin to decrypt them again. The malware spread around the globe Friday, before slowing over the weekend. By late Monday, cybersecurity officials said it had largely been contained, though governments and companies are likely to continue disclosing instances of infection for days or weeks as they get a better handle on the scope of the attack. Follow-on attacks are also possible. Britain’s National Crime Agency, a government agency which fights organized crime, said Monday that it hadn’t seen a second spike in ransomware attacks, but that didn’t mean there wouldn’t be one.

“We think the initial fire is put out,” said Rob Holmes, vice president of products at Proofpoint Inc., a Silicon Valley cybersecurity firm that tracks computer worms viasensors inmajor corporations and telecom companies. “The second thing is to make sure there’s no reignition of the fire.” A small number of affected users appeared to have complied with the ransom request, depositing payments—some as little as $300—into bitcoin “wallets,” essentially anonymous online accounts, designated by the hackers. But that total, just over $50,000 by late Monday, according to bitcoin trackers, represents a tiny sliver of the real cost of the attack. The ransomware threatened to destroy files if payments aren’t made. As long as those files are backed up, even that extreme outcome may not have huge financial costs. But companies rushed out information-technology teams all weekend to protect unaffected systems, restart attacked ones and assess the situation. In some cases, the computer paralysis had the potential to cause significant economic damage.

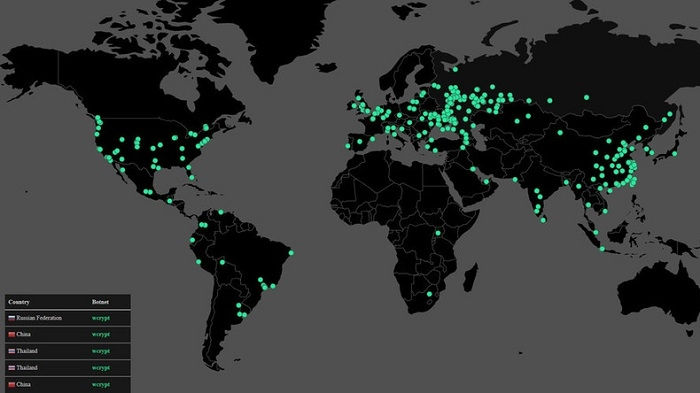

French car maker Renault SA shut down production at several auto plants across Europe over the weekend after being hit by the attack. It had restored all its plants except for one in France by late Monday, and expected that one back online Tuesday. A spokesman said the company would make up lost production and didn’t yet have a handle on overall financial costs. “It’s going to take some time,” the spokesman said. “They’re starting the calculations today. The priority was to get everything back up and running and now that’s done we are moving onto the analysis phase.” Britain’s state-funded health-care system, the National Health Service, was one of the first, and hardest-hit, institutions. The malware crippled computer systems at dozens of facilities, forcing hospitals to turn away patients or reschedule procedures. By Monday, a small number hospitals, including several in London, were still not ready to resume normal operations. Ben Wallace, U.K. security minister, said technology experts were working around the clock to restore NHS computer systems. “They have been working, I know, through the night almost to make sure that patches are in place to make sure so that hopefully this morning the NHS services can get back to normal,” Mr. Wallace told the British Broadcasting Corp. Monday. He said the U.K. government needed to assess why NHS hospitals and clinics hadn’t uniformly installed the patches that would have protected computers from the attack. The malware used vulnerabilities in Microsoft Corp. software and a tool that a group of hackers had previously made public, saying it had been pilfered from the U.S. National Security Agency. The agency has declined to authenticate the material. Microsoft has made available an emergency patch for operating systems that it no longer supports with security upgrades. Companies and users on newer systems who didn’t update with a patch Microsoft issued two months ago are vulnerable and raced to install them over the weekend and on Monday. The cyberattack hit businesses, hospitals and government agencies in at least 150 countries. Computer-security experts had forecast a wave of new disclosures Monday about attacks as users in Asia, Europe and the U.S. returned to work. Asia users, in particular, were mostly offline by the time the attack caught fire globally Friday, protecting them from the initial wave. Chinese state media reported nearly 40,000 public and private institutions had been hit in the country. The official Cyberspace Administration of China said victims included government agencies and private corporations and sectors including education, banking and information technology. European government computer-crime officials credited a British researcher with finding and pulling a “kill switch” lateFriday embedded in the malware, which slowed the spread of the attack. Proofpoint said Monday that there was a lot of traffic to the kill switch of the original worm, which meant individual computers were being infected but not entire networks. Ryan Kalember, Proofpoint’s senior vice president of cybersecurity strategy, said it didn’t appear as if a more dangerous strain of the worm, without a kill switch, was making its way around the world. Europe’s police-coordination agency estimated at least 200,000 individual terminals had fallen victim to the attack, while Chinese authorities put the number as high as one million world-wide. Tokyo-based Hitachi Ltd. reported system failures at locations in Japan and elsewhere that affected employees’ ability to send and receive emails. Hitachi said that it was working to try to resolve the problems and that it believed they were related to the ransomware.

In China, government agencies said their operations were affected as employees returned to work on Monday. Traffic police in Mianyang, a city in the southwestern province of Sichuan, posted a photograph of long lines in its office on its official Twitter-like blog and asked people to avoid seeking nonemergency services as its computer network remained down from the ransomware attack. Other government departments posted apologies about disruptions to services. Students at Dalian Maritime University in northeast China were among those affected by the ransomware over the weekend, a staffer at the university’s news department, who declined to give his full name, said Monday. Like other institutions, the university urged computer users to update their software, he said, and operations were returning to normal. CJ CGV Co., one of South Korea’s largest movie-theater chains, said it was hit by WannaCry. The company’s head of communications, Hwang Jae-hyeon, said the malware affected its advertising server, preventing ads from being displayed before the start of films at 30 locations. The attack hadn’t affected ticket sales or the company’s movie-screening schedule,

Comments